Lagged for Life

Hannah Brown and the storm-tossed voyage of the Broxbornebury to Botany Bay, 1814

On 1 December 1813, Hannah Brown, my great-great-great-grandmother, stood before the judges at the Old Bailey.1 She had been convicted of stealing a length of muslin, a shawl, and a cap, modest items, but enough to condemn her under Britain’s Bloody Code, under which over 200 crimes were punishable by death. The jury recommended mercy. Two months later, on 22 February 1814, her sentence was commuted to transportation for imprisonment. In convict slang, she had been “lagged”, sentenced permanently to exile.2 Although spared execution, Hannah knew she would never see her family again.

A Stormy Passage

Her voyage began on 22 February 1814, when she boarded the Broxbornebury, a three-decked merchant ship of over 700 tons under the command of Captain Thomas Pitcher.3 Alongside her were 119 other convicted women. Some travelled with infants; others, like Hannah, were young and alone. The ship also carried marines, soldiers, several children, and a handful of free settlers. Among the passengers was Jeffrey Hart Bent, a free man returning to New South Wales. His detailed journal offers a rare account of their perilous journey.4

For Hannah, the initial days at sea must have been terrifying. She had likely never been aboard a ship before. Below deck, women were crammed together in near-darkness while violent storms battered the Channel. The ship pitched and rolled, nearly colliding with another transport. Sailors and officers fought to keep the vessel afloat while chaos reigned in the cramped quarters below.

Below Decks

Conditions were appalling. The women endured days sealed in darkness, tossed violently in the rolling vessel as it battled monstrous seas. Seawater poured through ports, soaking bedding and clothing. They endured the noise of screaming women, crying children, and relentless seasickness. In the confusion, it must have seemed that drowning was a real possibility. Hannah, still under twenty, was now confronted with a reality far beyond the punishment decreed by the court. It is difficult not to feel compassion for her and her convict companions at this moment.

On 4 March 1814, the Broxbornebury limped into the Spanish port of Corunna.5 This unplanned stop saved lives. Bedding was aired, clothing changed, and fires lit to dry the lower decks. The ship’s Surgeon-Superintendent was Dr James McLachlan, who was known for his strict discipline and attention to cleanliness. He ensured that the crew distributed warm grog (one part water and one part rum)6 and fresh provisions to stabilise conditions. Departing Corunna, the ship sailed south along the Spanish coast, stopping briefly at Madeira, then Rio de Janeiro, before finally heading toward Port Jackson. The voyage lasted over five months.

The Long Voyage South

After leaving Corunna, life aboard was harsh, though relatively ordered for a convict ship. When the weather allowed, the women spent time on deck to get fresh air and sunlight. Most days were spent sewing, knitting, or quietly mending clothes. These repetitive tasks imposed a rhythm on the day and, for some, brought a sense of steadiness amid the unpredictable journey.7 Food, while basic, was regularly supplied, and efforts were made to ensure cleanliness and basic medical care. Despite limited space, many women formed bonds, finding small comforts and companionship amid the hardships.

Even so, the journey was perilous. Disease remained a constant threat, particularly during prolonged stays in ports such as Madeira and Rio de Janeiro. Storms forced long confinement below deck, worsening sicknesses and intensifying misery. Privacy was impossible. Vulnerability was unavoidable. Gossip circulated about improper relationships forming between some women and crew members. Such alliances, likely forged out of desperation or opportunism, offered additional provisions or protection. Hannah’s personal choices remain unknown, but given her youth and situation, it’s hard to imagine she could avoid unwanted attention entirely. We can only wonder if she found protection or preferred anonymity in an environment that offered few genuine choices.

Compared with other transports of the period, the Broxbornebury ultimately fared well. Unlike the notorious Lady Juliana, where most women formed alliances with crew members, conditions aboard Hannah’s vessel were somewhat better controlled.8 Only one death was recorded, remarkably low for a voyage of this length, highlighting the relative order and competence that distinguished the Broxbornebury from less fortunate transports. By contrast, the Surrey, which sailed in the same convoy, suffered a catastrophic typhoid outbreak en route, resulting in the deaths of 51 convicts and 17 guards, out of a total complement of approximately 280 people.9 The scale of this tragedy, among the worst in the history of convict transportation, underscores the vulnerability of these voyages and draws attention to the unusual competence shown aboard the Broxbornebury. Yet it also serves as a reminder of the vagaries of fate, such an outbreak could just as easily have struck the Broxbornebury, despite the best efforts of its crew.

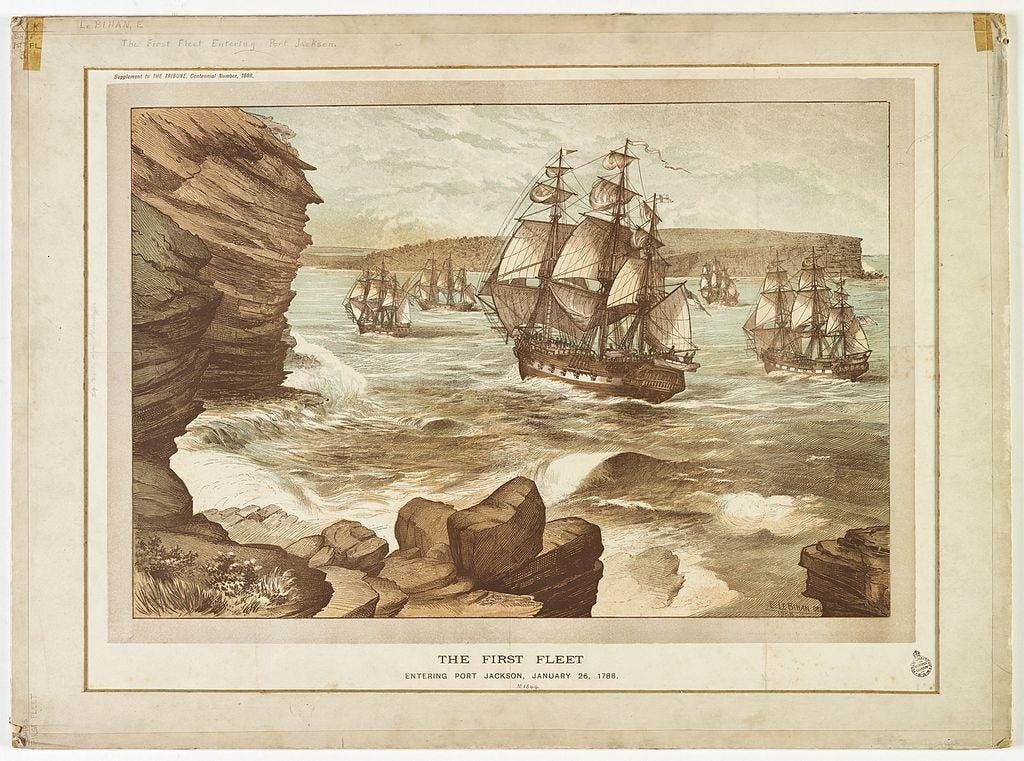

When the Broxbornebury reached Port Jackson in late July 1814, Hannah stepped ashore into a settlement still raw and uncertain. It was a small and scattered community, still clinging to Australia's coastline. She was now lagged for life.

My life in Australia begins with that moment: a young woman, exiled and alone, stepping into a future not of her choosing, but imposed by others.

Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org), December 1813, trial of Hannah Brown (t18131201-10).

The term “lagged” was common 19th-century slang meaning to be sentenced to transportation, especially for life. See Green, Jonathon. Green’s Dictionary of Slang, Vol. II. Chambers, 2005.

Bateson, Charles. The Convict Ships, 1787–1868. Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1983, pp. 141–143.

Bent, A Stormy Passage: Journal of a Voyage Performed on Board the Ship Broxbornebury from England to New South Wales, 1814, transcribed by Annie Lotocki (Suzanne & Waldemar Lotocki), Amazon, 2021, pp. 15–17.

Bateson, Charles. The Convict Ships, 1787–1868. Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1983, pp. 142.

Rodger, N.A.M. The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy. London: Collins, 1986, pp. 123–125.

Bent describes an evening on deck where the convict women “began dancing on the deck” to a fifing tune, continuing late into the night; similar scenes recur—“dancing,” “singing,” and playing forfeits—even amid the rolling seas. See: J.H. Bent, A Stormy Passage: Journal of a Voyage Performed on Board the Ship Broxbornebury, 1814, transcribed by Annie Lotocki (Suzanne & Waldemar Lotocki), Amazon, 2021, pp. 30–31.

Smith, Babette. A Cargo of Women: The Novel. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1988, pp. 15–20.

The Surrey sailed in the same convoy as the Broxbornebury in 1814 and suffered one of the worst typhoid outbreaks in the history of convict transportation. A total of 68 people died, including 51 convicts and 17 guards and crew. See: Charles Bateson, The Convict Ships, 1787–1868, Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1983, p. 142.

We owe so much to our convict ancestors Peter for the life we have today. To be convicted to transportation must have been a dreadful shock but then to have to endure such voyages is unimaginable. I cannot imagine what it must have been like for someone so young to know it was very unlikely that they would see family again. I do hope that you’re planning to write more of Hannah’s story.

Absolutely fascinating. I also had a relative on the Broxbornebury - not a convict but a passenger - John Horsely - the husband of my 4th great grand aunt. He emigrated but she did not - their marriage had broken down. https://anneyoungau.wordpress.com/2013/01/27/maria-champion-crespigny-born-1776-married-john-horsley/