In the early nineteenth century, the British legal system recognised more than two hundred crimes as punishable by death. Offences as minor as stealing from a rabbit warren, taking goods from a shipwreck, damaging a turnpike road, or concealing a stillborn child could result in the noose. So too could the theft of a saucepan, a roll of ribbon, or a loaf of bread. This “Bloody Code” was a system that ignored criminal intent, punishing those who acted out of desperation alongside those who sought personal gain. By inflicting the ultimate penalty, the law aimed to make an example of the poor and to deter further crimes. My great-great-great-grandmother, Hannah Brown, was one of thousands sentenced to death under this system when she appeared before the Old Bailey on 8 December 1813. Her story is neither unusual nor heroic. It reveals what punishment meant in her time, and how the same assumptions linger in present-day debates about crime and youth justice in Australia and elsewhere.

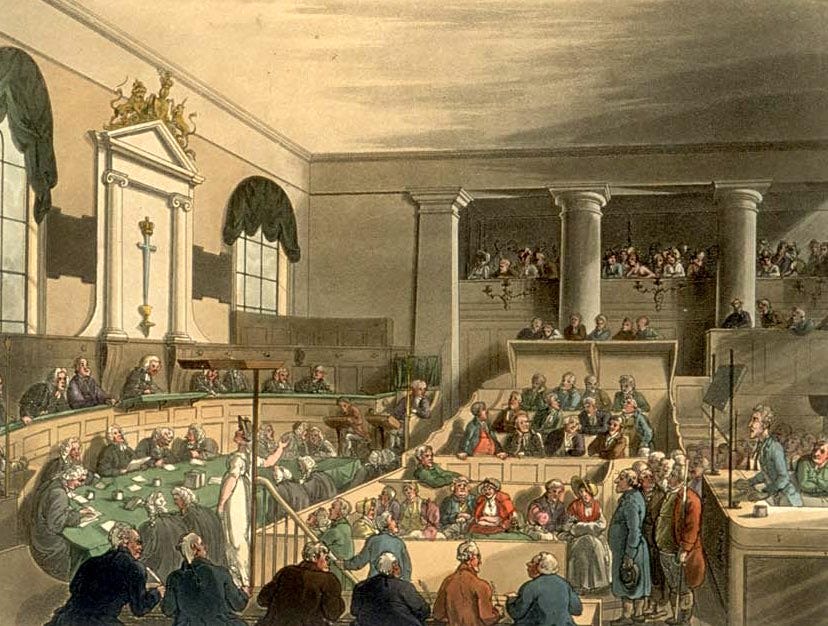

During the 19th century, the Bloody Code was on full display at the Old Bailey. Part courthouse, part theatre, it was the public stage where law, morality, and spectacle converged. The courtroom was packed, murmuring with tension; the judges in black gowns and bob-wigs sat high above the accused. Trials were quick, sometimes lasting no more than fifteen minutes. There was no legal representation, little cross-examination, and for the condemned, even less hope. The accused, bewildered, alone, and mostly poor, stood before the court. Hannah Brown was charged with stealing four yards of muslin, a shawl, and a yard of lace. None of the items were extravagant, but one exceeded the five-shilling threshold that defined a capital offence. The record of her trial survives:

HANNAH BROWN and SARAH DEERING were indicted for feloniously stealing, on the 5th of July, four yards of muslin, value 24 shillings, the property of Thomas Sonby, privately in his shop.

THOMAS SONBY.

Q: I believe you did not know the prisoner until the officers took them; after they had taken them was there any muslin produced to you?

A: Yes, which was my property.

THOMAS WHITLOW.

I am shopman to Mr. Sonby. On Monday the 5th of July, about two o’clock, the prisoners came into Mr. Sonby’s shop; they asked for Japan muslin. I showed them some sprigged muslin. They said it was too dear. They did not buy any. They went away.

Q: Did you miss anything?

A: I did not. About five o’clock, Read, the officer, came. He produced some muslin. I knew it belonged to my master. I had seen the piece of muslin in the shop three hours before the prisoners came in.

Q to Prosecutor.

The piece of muslin that was brought back by Read, was it yours?

A: Yes, it was. I had seen it the evening before. My house is in the parish of St. Andrew’s, Holborn.

WILLIAM READ.

I am an officer. I took the prisoners into custody. This piece of sprigged muslin I found in the bundle that was delivered up to me by Mr. Bennett, where they had committed another robbery in the city. Mr. Bennett, when he delivered it up to me, said they dropped it. This is the muslin that I showed to Mr. Sonby.

MR. BENNETT.

I am a linen-draper. The prisoners came into my shop, both of them, on the 5th of July, about four o’clock. They asked me for some muslins. I showed them some. They purchased a quarter of a yard of muslin. Soon after the prisoners were gone, I was called down; there was a shawl missing. I overtook the prisoners about three hundred yards from my shop. I brought them back again. Hannah Brown dropped from under her shawl a bundle; she dropped it on my foot just as I got them back again. This is the bundle that she dropped. I sent for an officer immediately.

Prosecutor.

This piece of sprigged muslin I can positively say is my property, by the private mark, and by the peculiar pattern. It is worth about twenty-four shillings.

Brown’s Defence.

It was given me. The other prisoner is innocent of it.

Deering’s Defence.

I am as innocent of it as the child in my arms. I always worked hard for my living.

Deering called four witnesses, who gave her a good character.

Verdict:

BROWN - Guilty - Death, aged 20.

DEERING - Not Guilty

[The prisoner, Brown, was recommended to mercy by the Jury, on account of the smallness of the property.]

Second Middlesex jury, before Mr. Justice Gibbs.1

The trial of Hannah Brown offers more than just a legal record; it captures a moment of personal loyalty, desperation, and rapid judgment. Hannah, although clearly implicated, insisted that her friend, Sarah Deering, was innocent. Whether this was true or a gesture of protection, we cannot know. What is clear is the speed with which both were tried, the absence of counsel, and the formality that masked a deeply unequal process. Hannah had no witnesses to speak for her, no one to defend her character. The item in question, four yards of embroidered muslin, was worth 24 shillings, enough to mark her crime as capital. Perhaps she dreamed of making a dress for herself. In the end, Sarah was acquitted. Hannah was sentenced to death.

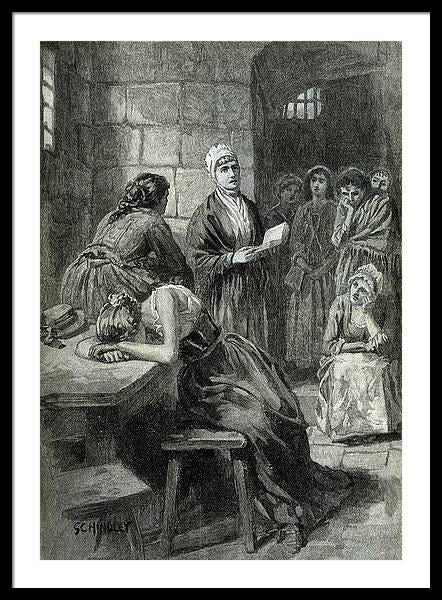

Hannah was sent down to Newgate to await her formal punishment and to learn whether the mercy recommended by the jury would be granted. Newgate was overcrowded and unsanitary, its cramped cells and wards filled with more than three hundred women and children, many sleeping on floors without bedding or cover. The air was foul, the walls damp, and vermin and lice were constant companions, spreading gaol fever and disease. Prisoners were required to purchase even basic necessities from the gaolers. In this dark confinement, Elizabeth Fry began her work in 1813: bringing clothing, scripture and rudimentary order, campaigning for separate wards and female supervision. Dostoyevsky once noted that the true measure of a society lies in its prisons. Newgate left little doubt about Britain’s moral standing in those years.

By the time Hannah was sentenced to transportation, the British system of convict exile had become a permanent response to overcrowded prisons and the loss of the American colonies. It had become a fixed feature of imperial administration. Hundreds of vessels had already made the long voyage to New South Wales, contracted by the government but often operated as private ventures. The dangers of these journeys were well known. In 1789, the HMS Guardian struck an iceberg en route and was forced to return to the Cape, badly damaged. The Matilda ran aground at Tahiti in 1791, and the HMS Porpoise was wrecked on a reef off the Queensland coast in 1803, though in both cases, most of those on board survived. The Second Fleet of 1790, managed by the slave-trading firm Camden, Calvert and King, became notorious for its neglect and high mortality, with more than a quarter of the convicts dying during the voyage. At the time, contractors were paid per convict who embarked, not per convict who disembarked, a policy that encouraged speed and minimised care. Disease, overcrowding, poor nutrition, and limited medical attention remained persistent risks throughout the early years of transportation. The passage to the colony, though increasingly routine, was still fraught with danger.

Hannah Brown was a young woman from my own family. The offence was real, but heartbreakingly small when weighed against the sentence she received. Her decision to steal was unwise, but the punishment tore her away from everything she knew. She was separated from her family, her country, and any hope of a familiar life. To think of her held in Newgate, awaiting word of whether she would live or die, and then consigned to the far side of the world, breaks my heart. Hannah’s story also raises questions we are still asking. If a society is to punish, then what should be the purpose of that punishment? How do we treat those who break the law, especially the young and the poor? In the absence of exile, how do we now reckon with crime and wrongdoing? Are we truly a more civilised society, or do we still deserve to be judged?

The degree of civilisation in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.

Dostoyevsky

Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 9.0) July 1813. Trial of HANNAH BROWN, SARAH DEERING (t18130714-29). Available at: https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/t18130714-29 (Accessed: 20th July 2025).

I love the way Hannah Brown's story is framed here. It left me wanting to know more about her and how she fared in Australia. It also left me wondering about Sarah Deering and what happened to her after she was released.

I love this story, altho it is appalling.

The illustrations, plus the details of imagery, make me feel I am there, hearing the tension and seeing the judges literally passing judgement from on high. I love the examples of what constituted a capital crime, chosen to illustrate how varied they are, by severity and by place -- a farm, the road, the sea, childbed.

And I love the unusual turn of phrase in "Her story is neither unusual nor heroic" - because we want to read about what is different and about heroes! Sort of daring us to read on, to kind of figure out why then you chose to write about it.

I love how you switch to the original trial transcript.

And how you connect Hannah's story to history with the descriptions of the other voyages.

Your description of her and her emotional situation makes me wonder what her life was life before, and what she made of it after.