As Catherine Cook, my great-great-grandmother, lay dying in 1856, just weeks after giving birth to her eighth child, it is hard not to imagine the thoughts that must have weighed on her. She was only twenty-nine. Her youngest, William, was still a newborn. Around her, the household would have been quiet, the children uncertain how to behave. Her husband, Thomas Mazlin, was facing what lay ahead with no real way to prepare for it. She would have known the risks of childbirth, and she had already buried three of her children. But this time, it was her turn to go.

Catherine’s death would have cast a heavy pall over the family household. As was customary, her body was likely washed and laid out in one of the family’s rooms, where friends and relatives gathered to pay their respects. Mourners would have worn black as an outward sign of grief and respect, and the home would have been filled with quiet conversation and shared prayers. A local Methodist minister probably conducted the service, followed by burial in a nearby cemetery. For the children, the experience must have been bewildering. For the youngest, their mother was gone, without explanation or return.

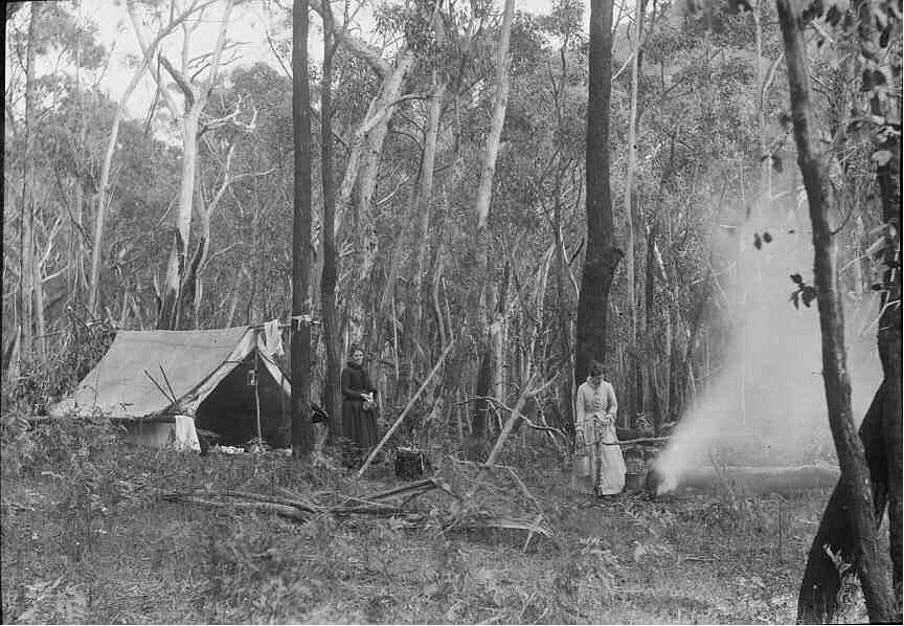

Hers was not an uncommon story, but one repeated in countless settler households. And yet, accounts like Catherine’s rarely appear in national histories. When we talk about a nation’s past, the focus often falls on stories of men: explorers, adventurers, generals, politicians, and captains. For a long time, pioneer women were kept in the background, their contributions overshadowed by the men who were seen to be shaping the nation. Yet their role was just as critical. They were homemakers, farmers, station hands, child carers, bush nurses, midwives, schoolteachers, small shop owners, and traders. In many remote communities, they were the only source of help. They advocated for their families, managed properties, supported neighbours, and became the backbone of settler society.

Catherine’s death and the earlier loss of three of her children were part of a wider pattern faced by women in colonial Australia, where access to professional medical care was scarce or absent. In most settlements, there were no doctors, no trained nurses, and certainly no hospitals. Instead, women relied on one another. Midwives, neighbours, and family members formed the only available safety net during childbirth, illness, and recovery. Pioneer women often delivered babies in bush huts, on verandahs, or on bare floors, using knowledge passed down through generations. They provided care, comfort, and practical help.

Changing Perceptions of Pioneer Women

For many years, the historical record treated women as passive figures, present but largely invisible in the broader narratives of settlement. However, modern scholars such as Marilyn Lake have reshaped that view, highlighting the strength and agency women brought to the challenges of colonial life. 1Their skills in managing families, running small farms or businesses, and keeping homesteads functioning were essential to the survival of fledgling colonies. Many women carried this responsibility alone for long periods when their husbands were away. Additionally, Patricia Clarke’s biography of Louisa Atkinson highlights how settler women navigated the challenges of bush life while contributing actively to the intellectual, cultural, and environmental understanding of a developing nation.2

Reflections on Pioneer Women’s Legacy

As we continue to uncover their stories through family records, letters, and new research, we begin to see just how central they were in shaping the early history of nations. Women like Catherine Cook, who endured the hardships of childbirth multiple times under challenging conditions, exemplify the strength and determination that were required to survive in the Australian bush. I am proud that she is my great-great-grandmother.

If you have stories of women like Catherine Cook in your own family history, I would be interested to hear them. How have you traced their stories, and what has helped you see their lives more clearly?

Lake, Marilyn. Getting Equal: The History of Australian Feminism. St. Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 1999.

Clarke, P. (1990). Pioneer Writer: The Life of Louisa Atkinson, Novelist, Journalist, Naturalist. Allen & Unwin.

It is easy to forget the pioneering women because it is often more difficult to uncover their stories ... But it is so important to try to try to find them and write about them. Early settler women were often remarkably strong and resilient women - They had to be. They travelled a long way in less than pleasant conditions and often on treacherous seas, on the promise of a better life. They arrived in places that seemed strange to them and raised a family in harsh conditions, often losing children to disease or accident along the way ...

What a coincidence, Peter, I’m working on a presentation on researching female ancestors. They require a totally different skill set than we use in researching males. Records weren’t kept in many cases or name changes make them more difficult to find.