One of the rewards of researching family history is that it draws you closer to people you have never met. Not in a sentimental way, but through a recognition of their efforts, their choices, and their strength. At first, like many family historians, I was energised by curiosity—curiosity about where I came from, and by the thrill of discovery: names, dates, family lines stretching back generations. But as I began to look more closely at individual lives, especially those of my Australian-based forebears, something changed. I found myself imagining what they endured and feeling a genuine sense of empathy. Although I had never known them, I began to recognise something of their character. That sense of connection surprised me and has stayed with me.

Two names from my own research come to mind: Catherine Mazlin (née Cook) and Robert Anthony.

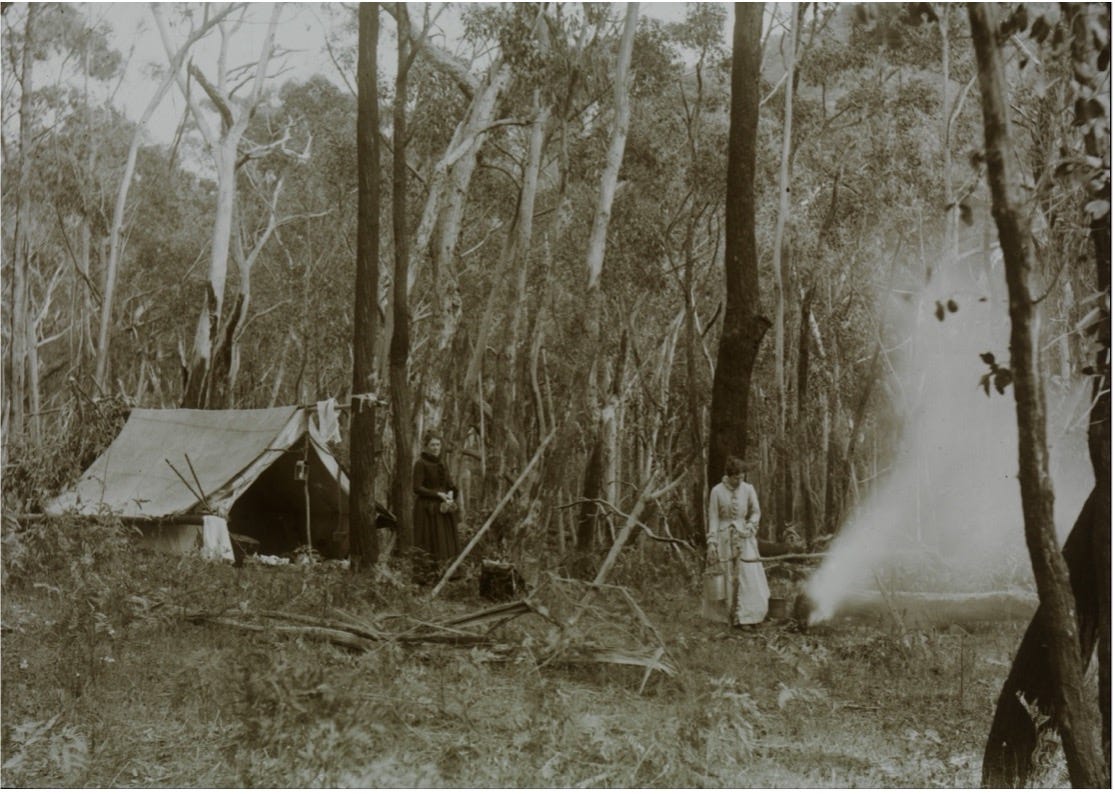

Catherine was the first wife of Thomas Mazlin, a currency lad, a timber-getter and the only child of two convicts transported to Australia in the early nineteenth century.1 They married in 1854, when Catherine was just fifteen years old. At that time, marriage at such a young age was not common, even in colonial New South Wales, though it did occur in more isolated or working-class communities. As a young woman, she moved into what was then bushland north of Sydney (densely forested, unsettled terrain with limited road access), helping to establish a household and raise children under conditions that were far from easy. The area, now part of Sydney’s northern suburbs, was in the 1850s still dense with scrub and trees, with limited road access and few established services.

Catherine gave birth to eight children. Raising a young family in colonial Sydney meant coping with isolation, poor shelter, and long periods of hardship, especially as the wife of a timber-getter, whose work took him deep into the bush, moving constantly in search of fresh stands of cedar and other marketable trees. The period from 1851 to 1853 must have been especially hard for her, as she lost her infant daughter Martha in 1851, followed by the deaths of her father and another daughter, Mary Jane, in 1853.

The cause of these deaths is not known, though infant mortality and infectious disease were common in colonial households at the time. Catherine herself died at the age of just 38. It is not hard to imagine what must have been on her mind as she lay dying: the fate of her children, the burden that would fall on her husband, and perhaps the hope that her mother, Sarah Cook, might step in to help. Sarah did. She took in the younger children and helped Thomas raise them, while the older ones remained in his care. Those first months after Catherine’s death must have been especially hard for Thomas. One of the older children, William Mazlin, is my maternal great-grandfather.

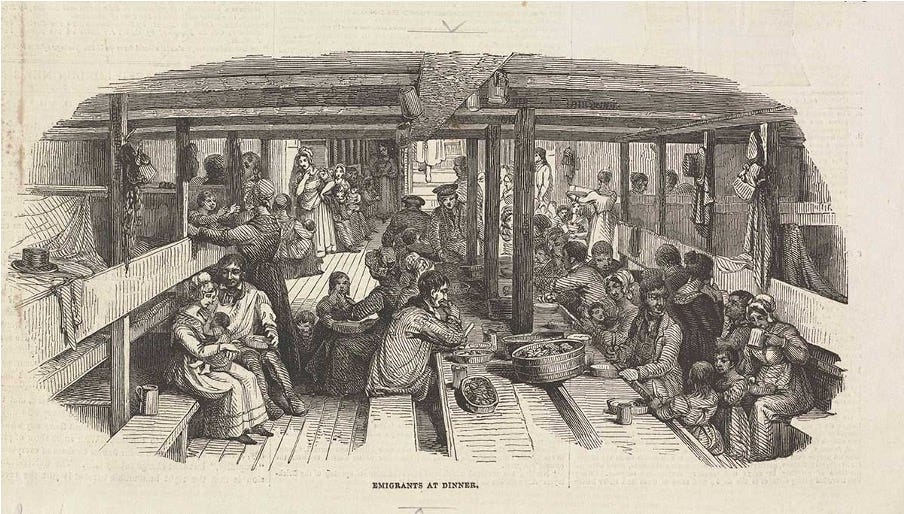

Then there was Robert Anthony, my paternal great-great-grandfather. He was part of one of the largest migrations of the nineteenth century, when millions of people fled Ireland during and after the Great Famine of the 1840s and early 1850s. In 1859, as a teenager, Robert embarked on the long journey to Queensland with his 12-year-old sister, Mary. They travelled aboard the British Empire, one of many immigrant ships encouraged and subsidised by colonial authorities keen to populate and develop the new colony.2 It was a perilous voyage of several months to the other side of the world.

I imagine him sitting beside her on the lower deck during a bout of seasickness or a stretch of rough weather, holding her hand as she cried herself to sleep, or quietly explaining to her what little he knew about the land that lay ahead. Conditions for steerage passengers on these long voyages were often cramped, damp, and poorly ventilated, with limited privacy or comfort. The image of this young man comforting his little sister says something about who he was: calm, caring, and dependable. He was her big brother.

In getting to know Catherine Mazlin and Robert Anthony, I feel more connected to my past. These people are not just dates of birth, dates of death, or vague outlines from the past. They are people I have come to know through the careful, though at times challenging, work of family research.

If you have undertaken similar research, you may know this feeling too—that moment when a distant ancestor begins to feel familiar. Have you experienced this yourself? Have you come to feel closer to someone in your family tree through the process of discovering their story? I would be interested to hear who they are.

Currency lads and timber-getters: The terms currency lad and currency lasses referred to a free-born child of convicts in early colonial Australia, distinguishing them from those born in Britain (sterling). It was once mildly derogatory but was later reclaimed with pride. Timber-getters, meanwhile, were bush workers who felled valuable trees such as red cedar and ironbark for use in construction, shipbuilding, and later railway development. Their work was mobile and physically demanding, often taking them deep into unsettled forest areas for weeks or months at a time.

Assisted immigration schemes: From the 1830s onwards, British and colonial governments introduced assisted immigration programs to encourage working-class migration to Australia. Passage was subsidised—often fully paid—especially for single women, farm labourers, and skilled tradespeople. These schemes brought over one million people to the Australian colonies by the end of the 19th century, dramatically reshaping the social fabric of the young settlements.

Yes, I feel a close connection to every person I have researched in depth. I feel like I know them intimately after delving so deeply into their lives, ... Not just my own ancestors (biological and adoptive) but also those of my husband and the many characters I am coming across in the course of my one-place study. And for those I know less well yet, there is a drive to find out more and know them better. In terms of shaping sense of identity, family and belonging, researching my biological ancestry has been particularly important.

The more I learn about my ancestors, the more I feel I know them.